- William Tyler Pours Himself Cereal Mullets

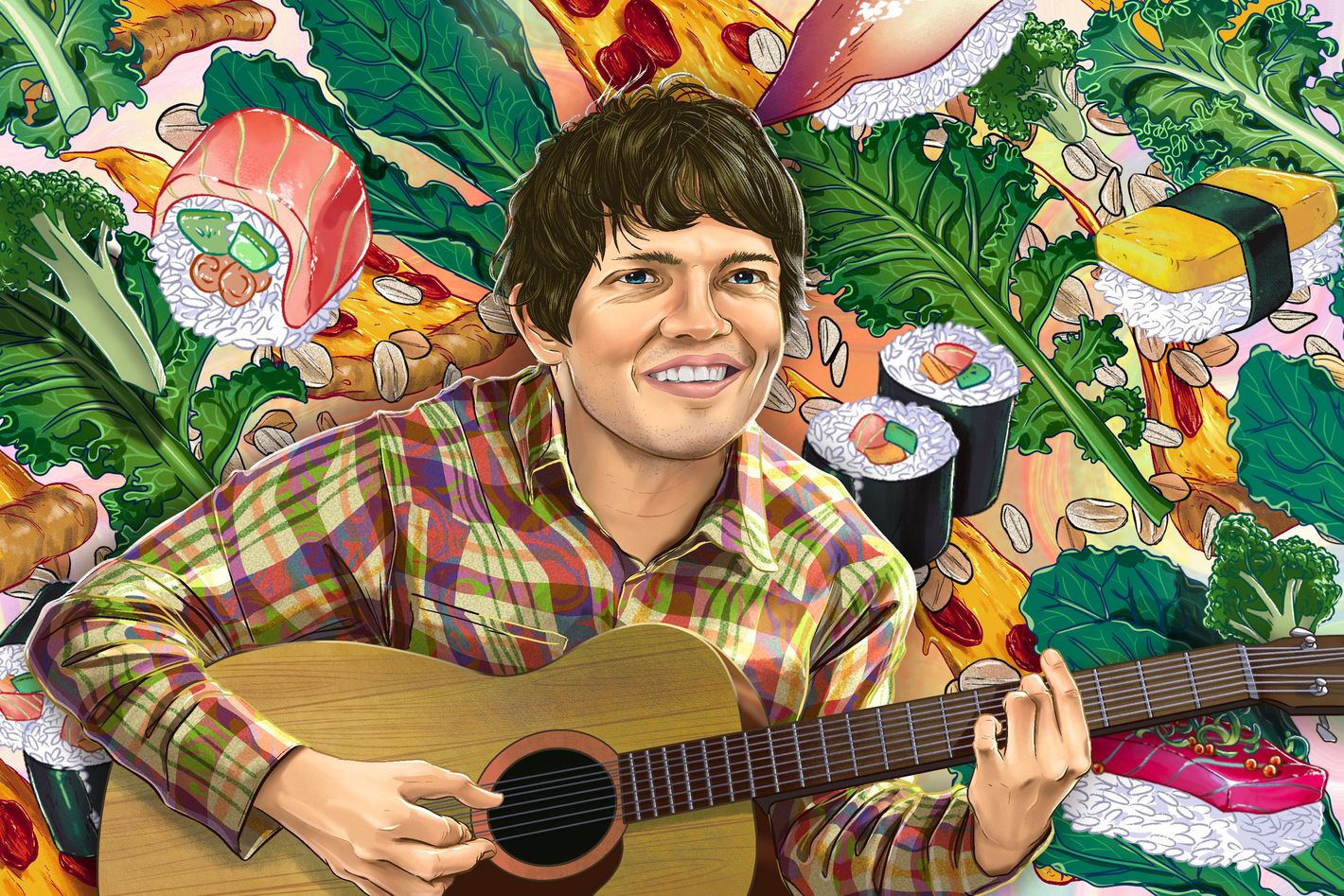

Illustration: Adam Mazur On records like Modern Country and Goes West, guitarist William Tyler manages to evoke a feeling of American vastness, a wide-open land filled with possibility. Through the use of found recordings, rusty static, and ambient texture, his new album Time Indefinite conjures a different kind of expanse, a world of individuals connected by distant analog AM signals broadcasting from who knows where. (He’s said, “It’s music about losing your mind but not wanting to, about trying to come back.”) Last month, Tyler, who lives in Nashville, came east for a listening party at Public Records and to take advantage of the things New York does best: Sichuan, sushi, and bagels. “To be diplomatic, I would say the bagels in Nashville are ‘Nashville good,’” he concedes, “but we also have barbecue that’s probably better than any of the barbecue in New York, so it evens out.”

Saturday, March 5

This was my first full day in New York. My buddy Jake Davies, who produced and engineered the new record, came with me. He’s only been to New York a few times, but I’ve been a lot. We were trying to set some goals for the trip. Whenever I’m here, I keep a checklist of things I want to do: go to an art-house movie theater, go to a museum, eat Sichuan food, go to a good Jewish deli, and maybe get a piece of pizza. If I do all of those things, it was a successful trip to New York.In the morning, Jake was itching for a bagel. We started looking around on Yelp, which is funny because people focus on the tiniest things to be mad about and then give someplace a one-star review while all the other reviews are five stars. We went to a bagel shop in Downtown Brooklyn that was next to the hotel. Jake got regular cream cheese and lox. I got tofu cream cheese, which is a delightful alternative you cannot find everywhere. That fueled us up for walking around the rest of the day.

We have another friend, Walker, who lives here. He suggested we meet up at the Met because I’d never been to the Met. I mean, we were only going to be able to see a fourth of it, but it’s still awesome. We spent a few hours seeing everything from haunted Egyptian stuff to very unergonomic musical instruments from the past to El Greco paintings.

I can fall into a rhythm in New York where I walk and walk all day and then eventually around six I get hungry and exhausted. That happened, so we stopped into a pizza place in the Upper East Side and each got a plain slice. We sat in a little booth where the side I was facing had an old cathode-ray TV sitting in a nook that was built for it. Something about it was very comforting: This is the oldest TV I’ve seen in use not at my parents’ house in a long time.

We had a listening party at Public Records that night. The rain was bad, and the turnout was impacted a little. It ended up being pretty chill, but everything sounded amazing on their sound system. I felt pretty good about that.

Afterwards we went to another place near the hotel called Moon Wok. It’s a Sichuan place and it was great. We ordered sautéed green beans, mapo tofu, soup dumplings, and Chinese broccoli. It ended up being enough food for five people. We ate as much as we could and then went back to the hotel with to-go boxes that weren’t going to fit into the mini fridge. Jake woke up in the middle of the night and ate some, so we got two meals out of it if you count late-night stoned eating. It was good insurance food.

Sunday, March 6

I went to a coffee shop near the hotel. I was by myself and I was feeling a little … I don’t know how ambitious I wanted to get for breakfast, so I had espresso and juice and I got an almond croissant because if there’s an almond croissant available I kind of have to buy it. I realized the thing was probably 800 calories. I ate a third of it and deposited the rest somewhere that I knew a bird would be able to finish it.We met up with a friend of ours, Martin, who runs Psychic Hotline. He’s the one putting out the new record. We went to Mile End Deli. I’ve been to Montreal a few times, and I’ve never understood why they have such a rich history with bagels, but I want to go back now because this was great. I had a turkey Reuben, Jake had chicken salad, and Martin got breakfast because it was that time of day where you can go for either lunch or breakfast. We don’t really have “deli culture” in the south, unfortunately. We have meat-and-threes, but those are very different and very not kosher.

So I checked “deli” off my list and for our last night in town we went to a sushi place called Sushi Gallery. Nashville has a lot of Japanese places and some of them are pretty good, but it’s not New York or L.A. This place was so adorable. It was two people, I assume a husband and wife, who own it, working behind the counter. She brought out the plates, did drinks, stuff like that. We were the only two people in there and we ate for two and a half hours. At this point, I only want to eat sushi in very cozy places; that feels like part of the experience I want to pay for.

Monday, March 7

We were flying back home, and I forgot to eat before the airport, which is usually my pattern. But since I have a lot of credit-card debt with Delta, I get to use the Sky Club a few times a year. In the LaGuardia Sky Club I had a couple of hard-boiled eggs and some potatoes and a cup of coffee and ran to my gate to get some airplane pistachios. This was lunch, and I think this is how you can tell the difference between someone who travels as a tourist and someone who travels so much that they’re a captive of the airline industry.We got back to Nashville and I wasn’t very hungry after flying. I have a habit of eating cereal for supper if I don’t have any other ideas. Since I hadn’t eaten any vegetables, I made a green salad and a bowl of cereal. I have a system where I try to mix a high-fiber, nutritious cereal and then mix in a fun cereal with it. I call it a cereal mullet. My go-to lately has been half a cup of Fiber One and half a cup of Cap’n Crunch. The cereal mullet is a good invention. It doesn’t add any nutritional value, though.

Tuesday, March 8

I decided to be brave and get a Nashville bagel. I got it from a coffee house I really like and where I used to work before I was doing music full time. It’s called Dose. I don’t know where they get their bagels, but they’re local and they’re actually very good. They have a similar texture to what you get in New York. They’re fairly satisfying.I was getting ready to leave again because we were having a listening event in L.A. and I was going to be there for a week. But I was at my folks’ house and my dad decided to make omelettes for lunch. My dad is one of those guys who is not, like, a kitchen person, but he cooks a few things perfectly. Omelettes are one of those things. It’s a situation where my mom will always be like, “your dad should be the one to cook the omelettes” and they’ve been together for 50 years or something so obviously they’ve got their thing worked out.

It was a light lunch with a salad, and night was a return-to-the-South meal. We ordered takeout from a local barbecue place called Edley’s. It’s kind of a local chain, but it’s really good. My folks got chicken and I got fried catfish with collard greens and coleslaw. Ultra, full-on southern.

Wednesday, March 9

When I moved back to Tennessee from California, the two kitchen appliances I brought were a Zojirushi rice cooker and a Vitamix. You can do so many things with just those two appliances. They’re not like iPhones: You can buy one of each and keep them for multiple generations. Breakfast was a green smoothie with spinach, kale, frozen fruit, berries, soy milk, and chia seeds. Honestly, man, sometimes that’ll keep me going till late afternoon.I was running around again, getting ready to leave and eating my version of the Paleo diet: handfuls of nuts and berries. It’s the lunch of the one caveman who has not successfully caught his own game yet. It probably means he’s going to be expelled from the tribe soon, which is a feeling I can identify with.

At night, I had a really nice dinner with my folks. My mom cooked salmon on the grill, and we had it with broccoli and spaghetti squash, which is a very underrated ingredient in my opinion. It conducts sauce very well. Not as well as actual spaghetti, but you can eat a whole plate of it. Being on tour is very antithetical to eating healthy, so I try to eat healthy whenever I can. I’m trying to be, like, a veggie-forward person.

More Grub Street Diets

- The Dog Days Are Over for Marlow & Sons

Photo: Joe Fornabaio/The New York Times/Redux Have you checked on your elder millennials this week? It’s been a rough one for our lost generation. First the Pencil Factory in Greenpoint announced its closure after 25 years, and on Monday, Marlow & Sons, a micro-generation’s date-spot-slash-proto-co-working-space, said its preemptive farewell after 21 years as well. (It remains open through Sunday.) Two decades in business deserves a victory lap, not tears, but if you remember where you were when Night Ripper came out, your inboxes will have filled with lamentations and reminiscences. Mine did.

“I’m just watching that 2008 Ford Edge commercial and crying,” texted my friend Celia, whose first date with the local indie-rock bassist on the rise had been at Marlow way back when. Oysters, wine, bread, and cheese — “the original girl dinner,” she told me. I had to confess I wasn’t familiar with the apparently canonical car ad, but there it is: pitched directly at the youngish and hip, at the moment that “Williamsburg” as a trope was breaking through to the mainstream. A gang of friends piles into their Edge, beep-boops an address into their primitive GPS, and, as Band of Horses plays in the background, off they go. Our heroine, doe-eyed in the backseat, is enraptured by the city as seen through the moonroof, so much so that she forgets to get out at their destination: Marlow & Sons. (It goes without saying that no one who lived in Williamsburg would’ve actually driven an Edge.)

Marlow was the second restaurant from Andrew Tarlow and Mark Firth, who helped codify the idea of the new-old Williamsburg restaurant with Diner a few years before. If Diner was the restaurant that made the neighborhood, Marlow was the everything-else complement: “a commissary/newsstand/tavern/oyster bar,” wrote The New Yorker, with a kind of out-of-time energy — “pure ironic-nostalgic pastiche.” That would have been cringe — not that we’d have called it that back then — but for the fact that the food was simply, excitingly good: piles of oysters; snout-y, nose-to-tail piggery (the Marlow group soon had its own in-house butcher and then its own butcher shop); chalkboard menus; flattering low light. If the flacks and ad men of the ’50s had ‘21’ and the machers of the ’60s had The Four Seasons, the newly digital creative class had places like Marlow. There were the in-house celebrities, who were cooler than the big celebrities — this magazine noted the patronage of alt power couple Alexa Chung and her Arctic Monkey, “drinking too much at Marlow” — and the longtime staff, who had a local-celebrity glow of their own. “It really did have the reputation of being the greatest hang with the tastiest food,” says Natasha Pickowicz, whose first job in New York was as a pastry cook at Marlow in 2013. “You felt rich even though you were making minimum wage.”

That all was, we noticed suddenly and with a shock, more than 15 years ago. Celia’s got two kids and a house in Sullivan County with that first-date bassist. We made our way over to Marlow on Tuesday to find the bones we remembered and a place we really didn’t. Marlow’s menu had changed over the years, its rustic-tavern cuisine swapped at some point for Japanese, then into more of a casual café. For its final week, it’s open only 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. — no evenings, which at one point would’ve been inconceivable — and by the time we arrived at 1:30 p.m., the day’s sandwiches had sold out. What had happened, we wondered? But then, we hadn’t been in years. Even Ford discontinued the Edge after 2024.

Still, Marlow’s influence endures. If Diner seeded the idea of this kind of “Brooklyn cooking,” first to Manhattan, then to the world, Marlow helped pioneer the all-day café and the market that doubles as a restaurant, or vice versa. (Tarlow’s wife, Kate Huling, sold her occasional clothing and accessories collections there, including bags made of leather from cows that provided the restaurant’s beef.) Their cooks and servers and staff — if you cooked at one, you ended up cooking at the other — fanned out, forming a Marlow diaspora that still influences cooking in the city. Caroline Fidanza, its first chef, opened Saltie, her Williamsburg sandwich shop, before returning to the Marlow Collective fold. Sean Rembold, her compatriot and then successor, now runs Ingas Bar in Brooklyn Heights, a Marlowish place if ever there was one. The partners of the Hart’s-Cervo’s-The Fly-Eel Bar group all met at Diner and Marlow.

Our attempted Irish wake had run aground. So much has changed in these parts from the places that our little cohort loved and patronized: Dressler gone, the DuMonts gone, the Bonitas gone. Once upon a time, journalists visiting the neighborhood to scope out the new Brooklyn scene would be treated to colorful reports of “a cocaine dealer who sells vegan cheese” — “the kind of guy,” Tom Mylan, the Marlow butcher once said, “who makes this place tick.” The clock has probably stopped on that. We left Marlow & Sons and walked down the block to the butcher shop, Marlow & Daughters. We bought loaves of She Wolf bread and considered some $32 artisanal vinegar. Nothing lasts forever, but on the speakers overhead, Passion Pit was playing.

Related

- The Most Surprising Pastrami in New York

Photo: San Wei I am always happy to take credit for discovering a new restaurant through hard-won reporting methods like canvassing a neighborhood in bad weather, scanning social media for hours, and starting impromptu conversations with a lot of strangers. But sometimes, a great spot just gets handed to me, as was the case with San Wei, which I learned about when a friend texted me a photo of a food-court Chinese stall advertising — between a plate of garnished dumplings and Coca-Cola chicken on rice — a copiously heaped oblong sandwich, under which was written “best pastrami in town.”

Given the incongruity of the people making it, this claim required immediate scrutiny. I convinced some friends to drive me over in exchange for pastrami and Chinese food. One of them assumed we were headed to a Chinese “mall,” à la New World in Flushing, a fair conclusion based on my description and how many times we have done that in the past. But San Wei is located at Queens Center in Elmhurst, which is as close to a stereotypical suburban mall as you can get without taking a ferry. There’s a JCPenney, an Aldo, and, at the bottom of the escalator, past the conveyor-belt sushi, a true American food court anchored by a Chipotle, a Chick-fil-A, and a KFC. In their company lies the independently owned Burmese Bites and, as of two months ago, San Wei.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, the floor was swarmed with people in seats and waiting in long lines in front of the cheesesteaks and fried chicken. At San Wei, things were quieter and an available employee offered to help us make our selection. Pastrami on rye was a given, but the rest of the menu required more consideration. I didn’t even know about the ramen, for instance. After much deliberation, I ordered — in addition to the half-pound sandwich — the San Wei noodles, Chongqing noodles, Coca-Cola chicken, and some pastrami bao.

When I started asking questions about the origin of the pastrami fusion menu, the cashier directed me to a man working on the line who turned out to be the owner. While he forked a brisket out of one of the steam trays and deposited it on the cutting board, he told me they don’t actually make it from scratch, revealing only that it comes from “a third party.” When I asked why a Chinese restaurant would open with pastrami as one of its core proteins (it’s also served cut into cubes on rice), he replied, “I don’t really think of this as a Chinese restaurant,” pointing to the pictures of ramen and saying he added additional cuisines because he felt he could do them justice. “I just like to cook what is good.” As he cut dark-barked slices with a smooth sawing motion, another chef was expertly slapping and stretching noodles on the table behind.

Once the food landed, the pastrami did something I might have thought impossible: It overshadowed multiple bowls of noodles. The rye bread was soft, barely toasted, squirted with spicy brown mustard, while the portion of thickly sliced meat was enough to weigh it down in the center. It had the salty, peppery kick you’d expect but was leaner — and thus less tender — than the melting sample slices Katz’s cutters hand out while preparing sandwiches. I want to tell you this was the best pastrami I’ve ever eaten, but I can’t. “It’s as good as what they serve at the Mets’ stadium,” my friend said accurately.

But both bowls of noodles were excellent: The thick, flat hand-pulled San Wei noodles were tangled with egg and fatty pork in a numbing tomato broth. The thin noodles were another hit, spicy and peppery broth with a slick of red oil and nothing else.

The biggest surprise of the day was the pastrami bao, cubed meat in steamed buns with a squiggle of mustard and chile crisp on top. They were outstanding: zingy mustard and assertive chile oil balanced by the soft, sweet mitten of white bread holding everything together. The buns were just the right size for anyone who wants a taste of pastrami without committing to a full, nap-inducing sandwich.

The owner, who was happy to chat at the shop but didn’t return any of my follow-up messages, has further ambitions for San Wei. He told me during our talk that he has been developing a churro recipe and wants to add shrimp Alfredo to his menu next. I suggested he try making it with his shop’s hand-pulled noodles, and he nodded in agreement.

More Eating New York

- Fedora Is Reborn

Photo: Hugo Yu In a couple of weeks, a familiar restaurant in a very familiar space will, after laying dormant for a bit, reopen to the public: Fedora’s neon sign is flickering back to life, with new hosts at the helm.

It’s been just about four years since the black double doors and tiled entryway last welcomed bargoers, but the restaurant is far from forgotten. “The number of people who come to the door and are like, ‘Are you open? I want to come back to this,’ has been amazing,” says Andrew Dete, a partner in the new restaurant. “It’s been a few years, so we weren’t sure how many people would remember it. We were wrong.”

There’s a lot of history here. The space has Prohibition-era roots as Charlie’s Garden and was, from 1952 until 2010, operated by Fedora Dorato, an adored proprietress who was received with applause when she entered the restaurant each evening. Over the years, she ran the kitchen and the long bar, though well above the food and drinks, Dorato’s convivial, all-welcome-here nature was the main attraction. At 90, she decided to leave her post behind the bar and find a new tenant. The story goes that she selected Gabriel Stulman, another West Village goodwill ambassador, to lead it forward. Stulman glammed up the well-worn space with black leather banquets, brass railings, and low tin ceilings, while managing to keep the identity of a neighborhood hangout, with Brian Bartels, its familiar, ever-present bar director, as master of ceremonies. The restaurant, a casualty of the pandemic, closed for good in late 2020. For a blip, it seemed that 4 Charles restaurateur Brendan Sodikoff would be the next tenant, but instead, Dete and Christa Alexander — partners in St. Jardim, the wine bar and café on the same block — along with their wine director there, Basile Al Mileik, signed on to the location last year.

Fedora has always been defined by its leader and in this revival that person is Al Mileik. He’s been a fixture of the NYC wine world, particularly when it comes to low-intervention wines, for the last ten years, having worked at Reynard, the Four Horsemen, and most recently running St. Jardim alongside GM Noah Rubin. (Rubin will also be involved at the new restaurant.) Inside Fedora, Al Mileik points out the front corner of the bar, a nook under the building’s stairs that will serve as a cozy bar, where he imagines neighbors with drinks on the rail as they wait for seats to open up. Fedora’s list will put a focus on classical wines from Burgundy and Champagne, mixed in with bottles from emerging regions. ”For me, there’s a ranking of a standing wine versus sitting wine,” Al Mileik says. “St. Jardim is a little bit more standing wine. Here it will be slightly more sitting wine.”

Photo: Hugo Yu In keeping with the neighborhood-joint mentality, the plan is to reserve a good portion of seats for walk-ins, with a full menu from chef Monty Forrest, a New York native whom Al Mileik worked with at Reynard years ago and who most recently ran the kitchen at Le Rock. His food will skew European, though it will be free of ties to any specific country or region. Instead, his menu would likely have felt at home in any of Fedora’s iterations: He’ll offer a substantial wing-attached chicken cordon bleu with a salad of spicy greens (“It’s elegant, but it’s rich and it’s comforting,” says Al Mileik), and is working on dishes like spaghetti with clams and oregano, black-bass Provençale, and a roasted-beef culotte with carrots. No matter what makes the final menu, “the food is very anti-trend,” Forrest says. “It’s just really tried and true.”

Cocktails, from Ben Finkelstein, the bar director at St. Jardim, will lean classic, too, with an emphasis on craft spirits and wine-based ingredients like vermouth and sherry. But despite an appreciation for the restaurant’s history, the partners have made some noticeable changes. They even flirted with changing the name, “but the more we got in here and scrubbed stuff off the walls, we were kind of like, ‘It just is named Fedora’,” Dete says. So they hired the design firm Post Company (who worked on Raf’s and recently completed Caffe Zaffri), which encouraged the partners to think about the spirit of the place instead of the literal walls. That freed them to lift the dropped ceilings, introduce some color by way of burnt sienna-upholstered banquettes; warm, blonde wood throughout; and minimalist lighting. Mirrors line the walls, giving the room a new spaciousness, even though it seats all of 39 between tables and the bar.

One thing that hasn’t changed is an appreciation for art. The walls at Fedora have always been lined with photos and pictures, no matter the owner; Dorato kept framed images of regulars and celebrity visitors, while Stulman spotlit selections from his trove of black-and-white pieces with gallery lights. Here, the artwork, all selected by Dete and Alexander, finds more color, too. The first piece they purchased is a print of Florine Stettheimer’s “Liberty”, a post–World War I painting of people returning to New York, that they’d seen at the Whitney. “That really resonated for us,” says Dete. “It feels like time to get back to that optimistic vision of New York as a bustling, teeming, colorful place.”

More New Bars and Restaurants

- Where to Eat in April

Illustration: Naomi Otsu Welcome to Grub Street’s rundown of restaurant recommendations that aims to answer the endlessly recurring question: Where should we go? These are the spots that our food team thinks everyone should visit, for any reason (a new chef, the arrival of an exciting dish, or maybe there’s an opening that’s flown too far under the radar). This month: Scandi cooking that’s nothing like Noma, a beloved Malaysian chain’s surprising return, and a New American destination in a somewhat surprising part of town.

Liar Liar (Gowanus)

A friend swears she wasn’t lying when she said this wine bar, which occupies a corner space on a drab block across the street from a couple construction sites, would be easy to slip into on a Friday night. Unfortunately for my friend, the secret is out. By 6:45, it was jammed with people having drinks and waiting for tables up front. The squeeze, however, is worth it. There are glasses of Austrian Chardonnay and Croatian Riesling, the martinis are sharp and frigid, and a five-item food menu has an extremely high hit rate: Caesar salad with a creamy jolt of anchovies, a juicy and totally respectable burger, and a fried-chicken sandwich dripping with sweet-and-spicy sauce that tastes like Chinese takeout. Top billing, though, goes to steak frites. The bright red beef practically glows in au poivre sauce, and the dark fries (available solo, too) are hit hard in their bath of hot oil. At $30, it’s practically a deal in today’s New York dollars, but regardless, it’s money you won’t regret spending. —Chris CrowleyConfidant (Industry City)

Most people head to Industry City for a Costco run or to buy a discounted sofa at a furniture-store outlet. Maybe you should go for some tuna prosciutto: Chefs and co-owners Brendan Kelley and Daniel Grossman have opened what’s being billed as the first full-service dining establishment in the area. The duo met while working at Roberta’s, and they bring some of that restaurant’s freewheeling spirit (if not its pizza) to their new spot. “Potato and apple” is simply named, but by sphering the apples into candy-sized pieces and serving in a thick, horseradish soubise, it’s surprisingly textural. An excellent prawn potpie is served more like a seafood bisque with a pastry popover. Dessert brings malted mille-feuille, a pyramid that is as satisfying to smash with a spoon as it is to eat. —Zach SchiffmanHildur (Dumbo)

“Beers with the fellas,” “wings with the fellas” — have you tried meatballs with the fellas? At this new Scandi-Brooklynite restaurant from Emelie Kihlström and Elise Rosenberg of nearby Colonie in the old Gran Electrica space, such innovations are possible. (Kihlström and Rosenberg ran Gran Electrica, too, but Hildur may be a little closer to home — Kihlström is Swedish, and Hildur is her grandmother.) We gathered there recently, the former roisters of my youth, now harried dads. Maybe it’s the Ingmar Bergman of it all, but nutmeg-laced meatballs with lingonberries and pickled herring gone almost pastry-sweet in its dressing of brown butter were better-than-expected complements to misty reminiscence. The room has been stripped down to a lighter, more elegant minimalism, and the cocktails — poured by much the same front-of-house staff neighbors will remember — are the right kind of clever (try the mirepoix martini, infused with carrot, celery, and shallot). As date nights flickered around us, the fellas gave high marks to the Barbie-pink Swedish princess cake. —Matthew SchneierKabawa (East Village)

The debut of Momofuku’s Bar Kabawa earlier this year was something of a warm-up to the full Kabawa. Now, the just-opened next-door dining room, wrapped around an open kitchen as it was when the space housed Ko, is offering a full menu of Paul Carmichael’s pan-Caribbean cooking. Orb-shaped cassava dumplings hide in an onion-heavy Creole sauce, a sausage of “jerk duck” is like rough-hewn boudin, goat curry is enriched with fish sauce and dried scallops, while pods of fresh tamarind are gifted to be unwrapped before dessert. The fruit inside is chewy, sour and sweet, “like pâte de fruit, but with a pit,” Carmichael joked as he handed them over the other night. The chef is a natural M.C.; get a seat at the counter to say hi. —Alan SytsmaPapparich (Lower East Side)

To the delight of many who lamented the closure of the Flushing location a few months ago, this Malaysian chain, with over 100 shops around the world, has reappeared on Ludlow Street. Malaysia’s cuisine references almost every South Asian country, which makes for a menu that is familiar, but with a twist, perhaps in the form of a dose of shrimpy sambal that coats stir-fried okra or string beans with plump shrimp as densely as Takis. Hot roti, meanwhile, shatter on the outside and emit butter-scented steam upon tearing — an order of two with dhal is just $10. There were leftovers from a $16 bowl of curried chicken laksa loaded with thick egg noodles, sliced chicken, tofu puffs, and fried eggplant. An order of beef rendang is stewed until the sauce becomes a caramelized reduction of grated ginger, garlic, lemongrass, and chiles, while relatively mellow beef wat tan hor, wide rice noodles partially submerged in gravy marbled with an egg, has the flavor of lo mein. Dessert is a cup of white coffee, made with butter-roasted beans and enriched with condensed milk, that can be ordered hot or iced. —Tammie TeclemariamMore New Bars and Restaurants

- Bryant Park Grill’s Operators Are Suing to Prevent a Jean-Georges Takeover

Photo: Shutterstock Last October, the people behind the 30-year-old Bryant Park Grill rang the emergency bells: Help save our restaurant. The operator, the publicly traded company Ark Restaurants, learned that it was likely getting the boot to make way for celebrity chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten and Seaport Entertainment. The Bryant Park Corporation (which leases the space) revealed in January that it was awarding the restaurant to the latter group. Now, the end is near. Ark’s lease for the Porch, an outdoor space, expires today. Its lease for the Grill is up at the end of April. But its CEO, Michael Weinstein, isn’t going down without a fight. Today, Ark filed a lawsuit against the BPC over “a sham bidding process” that favored “an inferior bidder” in Vongerichten and Seaport.

In its complaint, Ark argues the court should uphold the group’s “rights to a lawful and proper bidding process” and declare that “Bryant Park belongs to the people” and is not the “private property” of BPC and its president, Dan Biederman. “Dan has made Bryant Park his own little fiefdom,” Weinstein says. “He did 26 million bucks in revenue in the park last year. It is no longer a public park, it’s a business.” The BPC (originally the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation) was founded in 1980 and by 1983 had proposed an $18 million redevelopment of the park that included a security force and “huge glass restaurant.” It was a celebrated transformation, even as people raised concern about the public-private partnership. Today, “Manhattan’s Town Square” offers woodcock watching and an online store with $550 vintage park chairs, and hosts the crowded, Bank of America–sponsored holiday market. Ark has been involved since 1995 when it opened the Bryant Park Grill. It’s one of the country’s top-grossing restaurants, and combined revenues for its three park businesses — which also include the Porch and Bryant Park Café — amount to $28 million a year.

In 2023, the BPC posted a request for proposals from restaurateurs interested in leasing the spaces. While Biederman — who has no comment on the litigation but “looks forward to welcoming Seaport Entertainment Group” in the coming months — says that 11 restaurants were seriously considered, Ark alleges that “it had become clear that BPC were positioning Seaport to prevail.” The suit also alleges that the Seaport bid offered $1 million less in annual rent, while also receiving extended operating hours and $2 million toward planned renovations. Biederman himself has seemed to back up this allegation: “This city and others very often go for the highest rent offer, and we said, can we afford not to do that?” he said in a December meeting of the local community board’s parks and public spaces committee.

Vongerichten is one of New York’s most famous chefs, and his cachet allows him to charge high prices. (A six-course dinner is a steep $298 before tax and tip — a step below the priciest restaurants in the city.) It’s obvious why any landlord with a prime location might want to do business with him, given his pedigree. But Ark says Vongerichten is only the public face, and that the restaurant will be run by Seaport Entertainment, which it argues “has no record of operating a successful New York restaurant.” The two partnered on the Tin Building, a splashy, expensive revamp of the old Fulton Fish Market building. At the time, the cost to build it was touted as $194 million, although it’s unclear how much of that went to rebuilding the pier. More pressing is the fact that the operation has lately been losing Seaport Entertainment over $100,000 a day and shedding labor. Ark’s 250 employees at the Bryant Park Grill will undoubtedly need to look for other jobs, as the restaurant will close for at least a year of renovations.

“You’re doing a deal with Seaport, you’re throwing out 250 employees, and you’re accepting at least $1.2 million, $1.4 million less in rent. Who does that?” Weinstein says. “It’s a disaster for the park.”

Related

- The $15 Cocktail Is Back, Thank God

Photo: Justin Sisson/ Will Wyatt, an owner of the cocktail bar Mister Paradise, was on a bar crawl in London with a fellow bartender recently when he had a revelation. “We were bopping around,” he recalls. “We were both a little burnt out on the over-inventiveness. Went to all the places we were supposed to go: Tayēr + Elementary, Bar With Shapes for a Name — intense programs.”

They ended up at Satan’s Whiskers, a casual bar on a scruffy block in the Bethnal Green area. The menu was all classic cocktails, priced around 12 or 13 pounds. “The first thing we see is a coconut margarita,” Wyatt says. “We drank those all night.” Then, “we talked about other things, not the complexity of what we are drinking.”

Wyatt has brought that same spirit to the East Village with El Camino. There are eight drinks on the menu, including a negroni, gin-and-tonic, martini, and — as an homage — coconut margarita. Everything costs between $13 and $16. There are two beers, Guinness and Estrella, 11 wines, and some snack food. As for décor, Wyatt and his partners designed and built the place themselves, including the sign outside.

In an era of $22 drinks and cocktails designed to taste like pizza, roast chicken, or hot dogs, there may be a correction coming: A handful of seasoned owners are putting the brakes on the ever-accelerating cost and cleverness of the average mixed drink, leaning instead into familiarity, accessibility, and value.

One of the names embracing this new austerity might be surprising: Death & Co — among the city’s most prominent neo-speakeasies and now a national chainlet of high-end bars — is introducing a “fast-casual concept” called Close Company that will open in Nashville, Atlanta, and Las Vegas in the coming months, with a New York outpost in the works. Drinks there will hover around $15, and the spaces will do away with many of the hallmarks of the modern cocktail bar. There will be no host greeting guests, no seating-only setup, and no reservations needed. “It will feel a little less precious, a little more fun,” says Dave Kaplan, one of Death & Co’s founders. “It’s this idea of a cocktail bar that is more of a neighborhood bar.”

In Chicago, Kevin Beary, who is beverage director of the tiki bar Three Dots and a Dash, saw a similar opportunity to open something simpler — and cheaper. “I’ve been growing increasingly concerned that the newest generation of drinkers are not consuming cocktails,” he says. “I think it could coincide with how expensive cocktails have gotten in bars and restaurants.” He opened Gus’ Sip & Dip on New Year’s Eve with a menu of classics — Cosmo, mojito, Sazerac — and a line at the top that reads like it’s from 2008: “All Mixed Drinks — $12 ea.”

Of course, keeping prices low for customers means keeping costs down for the bar. One spot due for a cutback is inventory. Over the past 20 years, a gleaming wall of back-bar bottles has become a signifier of mixological seriousness. Close Company will carry one or two brands of vodka instead of ten. At Gus’ Sip & Dip, which has a wraparound bar, there isn’t even a back bar for customers to eyeball. “There are 38 bottles in the well,” says Beary. “One vodka, one tequila. We don’t have a bunch of inventory sitting around.” With fewer options, Beary can order what he needs in larger quantities at a discounted rate.

Close Company also plans to save money on construction materials: The new bars will have poured-concrete floors instead of wood, and vinyl banquettes instead of leather. El Camino, meanwhile, sits next door to HighLife, a burger joint that Wyatt and his partners opened in February. Because the businesses share an address, the various costs concomitant with maintaining a building can be shared.

Working harder to keep prices down may seem counterintuitive, but operators who have taken a similar approach have seen the gamble pay off. When the veteran cocktail-bar owner Erick Castro took over a San Diego dive named Gilly’s in 2023, he gave the space only a cursory glow-up, improved the cocktail program, made on-site games like pool free, and quickly reopened with $12 drinks, all ordered at the bar. “You’re not getting a table-side negroni,” he says. “We sell beef jerky and chips.” Business has been gangbusters ever since. “We didn’t spend a lot of money, didn’t have a lot of costs to recoup,” Castro explains, “so we could keep the prices low. Our guests don’t have to make up that cost.” (Drink prices have, however, risen — to $13 each.)

Wyatt learned at Mr. Paradise that something like El Camino might be feasible. When cocktail prices started to climb a couple years ago, Mr. Paradise followed the trend, bumping the average menu number from $16 to $18 per drink. After a while, Wyatt brought the prices back down to $16 — and sales went up. “That two dollars made a difference in enticing people to say, ‘You know, I’ll have another round.’ It causes people to not be as calculating. People started picking up rounds.”

Lowering prices also eliminates a kind of anxious expectation that comes with higher-priced drinks. “If I’m paying $18 to $22 a cocktail, I want a seated, calm experience with the people I’m with,” Kaplan says, “and I want that cocktail to be really, really great. If that attention to detail isn’t there, I’m going to leave a little frustrated.”

None of this comes as a surprise to Kevin Armstrong, one of the founders of Satan’s Whiskers, the London bar that first inspired Wyatt. “Money is hard to earn,” he points out, “and guests appreciate businesses that offer consistent and exceptional value.” When he opened, Satan’s Whiskers was far off the beaten path, but low rent allowed Armstrong to attract customers in another way: “We needed to be affordable enough that people could return to us several times in a week, should they choose.”

Does Beary think a shift to more affordable drinks will anger competing operators who might see their own drink prices as being undercut? When I ask him, he gives a chuckle. “I think there’s a lot of interest,” he says. “People are intrigued. Maybe people are angry about the prices, but I’d so much rather sell you two cocktails instead of one cocktail for the same price and have you leave satisfied.”

Related

- Why Martinis Keep Getting Dirtier

- Natural Wine Grows Up

- The Best Bar Crawl in New York, According to Karen Chee

- Ella Emhoff Likes a Sugar Burst

Illustration: Maanvi Kapur Ella Emhoff launched her Substack, Soft Crafts Craft Club, in late October of last year, just as her stepmother rounded off her presidential campaign. Five months later, she’s shed her Secret Service detail and is trying to rediscover her voice through her art and writing, shepherding an online — and charmingly intergenerational — community of crafters. “A lot of my demographic is not 25-year-olds,” she says. “And I love hearing from people and seeing what they’re making.” This week, in between both work-hobbying and hobby-hobbying, she took care of her sweets fix, ate homemade tomato soup, and had a very lawyer-dad-friendly lunch with Doug.

Wednesday, March 19

I start the day off with an iced coffee and a splash of oat milk from my local coffee shop. There are a lot of regulars from the neighborhood, so it’s sort of like a meeting ground for everyone to hang out. The barista has conversations with everyone, and the line can get pretty long; people from other neighborhoods have complained to me about the service. I’m like, “Actually, it is the best service I have ever had at a coffee shop.”I also buy a cinnamon-chocolate-chip scone. They are unreal, and, consequently, always sold out, so you have to get there early.

I always keep treats around the house as little sugar bursts. I have the classic old-lady bowl of hard candies — cinnamon discs, Maoams, and chewy Mambas. Four years ago, my mom read that eating gummy bears cures mercury poisoning (?). She started eating so many gummy bears, and I just … followed suit. I have been changed ever since.

Later, I have some Berocca. It’s basically the European version of Emergen-C, and I really don’t know the difference. I do think it tastes better; today, I have the cassis flavor. It gives me a good boost, and it’s got a lot of immunity stuff in it. I also add collagen powder, and sometimes I’ll throw in some greens powder.

Lunch feels like a Chopped challenge. I have a random loaf of refrigerated bread, a can of tuna, green onions, and a fridge full of spreads. I mix the tuna with green onions, lemon, vegan basil aioli, and absolutely no mayo. I like to call this intuitive cooking.

Whatever I have in the fridge, I will find a way to use it. I’ve been ordering from Misfits Market for almost a year and a half now. It’s sort of like I’m doing my normal grocery shopping at a Whole Foods — but cheaper. Even the produce — which I initially assumed would be pretty banged up — is solid. Earlier in the day, I was roped into joining my friends’ bowling team for the Nolita Dirtbag Tournament at the Gutter. I thought it would be a quick thing so my boyfriend and I could grab a full meal afterward, but I quickly realize that is not the case. Upon walking in, I see everyone is wearing matching bowling shirts. A six-foot, flame-lit trophy sits in front of a giant bracket.

There’s a lot of yelling, and a lot of grown men getting really intense about bowling. I never like to toot my own horn, but I’m a pretty good bowler, so I’m excited. (We don’t make it past the first round.)

They have an open bar, so I have many bottles of Stella Artois before heading to 7th Street Burger, where I get a double burger and a side of fries.

Thursday, March 20

Coffee with almond milk. I usually try to make my coffee at home, but it depends on the quality of beans that Misfits Market sends me for the week, which can be variable. This week, they don’t cut it.I’d call myself an intermittent coffee drinker. I don’t really need it. I just like the act of drinking it. I also grab another scone, this time straight out of the oven.

I get a very last-minute text from my dad asking to have lunch with me and my boyfriend. Doug doesn’t live here full-time, but he’s often here for work. We hop on the train and meet him at Rue 57, which really feels like a proper business-lunch place — the kind of restaurant that screams lawyer-dad. The food is pretty standard. Both Doug and my boyfriend get the chicken club — which is what I want, but I feel like we can’t all get the same thing, so I get a chicken Caesar salad and an unsweetened iced tea. It’s okay, but I always want more from a Caesar salad.

We hop on the F train later to go to Dover Street Market for my friend Luisa Opalesky’s photo-book launch. It’s packed. Dover Street events are always a little funny; the layout of these stores never quite seems conducive to having a lot of people in them, so you’re often having to navigate traffic jams. It’s a lot of realizing that someone you know well was three feet away while you’ve spent an hour trapped in a corner.

On our way out, we realize we’re in dire need of dumplings and cabbage, and Mission Chinese never disappoints … except when they’re out of broccoli with beef cheeks, which they are on this night. Regardless, whenever I come here, I order everything. Tonight, it’s the smashed cucumber salad, addictive cabbage, Chongqing wings, soup dumplings, and beef chow fun. I could eat those wings and cucumber salad forever.

We get the Pop Rocks passion-fruit panna cotta for dessert. After dinner, we walk our leftovers home in the pouring rain, but, fortunately, our food is spared …

Friday, March 21

… Or so I thought. I wake up and realize that my boyfriend has left them on the counter all night. He insists they should be fine, but I’m not so sure. Leftovers, at most, only get a couple of days in my fridge, if not one.Iced coffee with oat milk. I guess I do really frequent this coffee shop. No scone, though. After our Mission Chinese feast, I need some time to build up an appetite.

For lunch, I have a mug of homemade tomato soup. Sometimes, on Sundays, I’ll meal prep a bunch of soup for the week. This week, I roasted two beef tomatoes, a container of yellow cherry tomatoes, two red bell peppers, and four cloves of garlic, seasoned with salt, pepper, and oil. I let them get nice and juicy in the oven, slightly crispy on top.

I spend the afternoon working at home and cleaning the apartment. When it’s cold and rainy, I like to hibernate. I also know that once summer hits, I am going to want to be out and about all the time, so I’m trying to get as much done as I can. I just relaunched my knitting club on Substack — it’s more of a crafting club now — after putting it on pause during the campaign, but now I’m bringing it back, and that’s meant a lot of work and a lot of meetings.

My boyfriend comes home with a half-dozen Dun-Well doughnuts — blueberry glazed, maple, apple crumble, triple chocolate, and lemon glazed. We take little bites of them all. I’ve been PMS-ing a lot; he thinks I need something sweet, and he’s right. Dun-Well makes vegan doughnuts, and I’ll say it: Vegan doughnuts are better. They’re lighter and more refreshing.

My mom also happens to be in town, so we go out to dinner with her at one of our favorites, Cosme. We’re creatures of habit with restaurants we love — it’s hard for us to break out of our routine and not order the things we know will hit. I’ve been trying to prove to my mom that orange wine is really good, but on our last visit, I ordered a glass that the sommelier described as “very garbage-y and sulfury.” Needless to say, my mom remains unconvinced. So we opt for mezcal margaritas and order herb guac, uni bone marrow tostada, prawn al pastor, striped bass, and duck carnitas, which are the stars of the show — a giant piece of perfectly cooked duck covered in radish and cilantro, with green tomatillo and red salsa on the side. So good.

Saturday, March 22

I get another iced coffee from the shop, and then my boyfriend and I run around Soho on some errands. We eventually need food, and the only spot that has outdoor seating that allows me to bring my dog, Jerry, is Jack’s Wife Freda.I don’t want to jump on the bandwagon of being like a Jack’s Wife Freda hater … but this particular experience is just not fun. We order the burger and the green shakshuka, but it’s a weekend brunch so it takes a while to get our food; when it finally does arrive, I am pretty underwhelmed.

Then, midway through our meal, it starts raining. Once it stops, we have a brief sit in the park before realizing we need to go home and get ready to go to our friend’s concert at Berlin Bar. The show is very early and extremely on time. They tell us, “Doors open at 7; we’re on at 7:30,” and they are on at 7:30. I can’t believe it.

The show is synth-y and funky. Our friend — his band is called Teardrop — wears a latex mask while he performs. Friends’ shows are always a toss-up, but I am very impressed by the stage presence. We stick around and watch the next band. They have an early-’80s sound and wear all-white suits and … plastic clear masks. Something must be in the air.

Afterward, six of us go to Bar Valentina. I never expect to get a table anywhere downtown, but fate is on our side — just around the corner from the entrance is a perfect six-top. Right as we settle in, my friend sets her phone on the edge of the booth and it falls into the crack. My other friend uses her flashlight to try to find it — and her phone falls in too. The booth is bolted into the floor, so we have to buy a grabber at the bodega next door. We share fried zucchini chips, and I order a Caesar salad with fried chicken. Let the record show, this one is way better than the last.

Everyone is going to an apartment in Bushwick, but I head home. I usually do not go out very much, and having a dog has only fed that instinct, because I get to be like, “Ah, I don’t know if I can come — Jerry’s at home.”

Sunday, March 23

We wake up and go to Betty, a truly perfect Sunday brunch spot. I usually get the You Betty Be Ready, which is a dealer’s choice of scrambled eggs, bacon, pancakes, and potatoes. It’s a lot of food; it keeps you going all day. This morning, though, I don’t wake up very hungry, so I order buttermilk banana pancakes and an oat milk cortado. I usually try to avoid dairy, but I tend to microdose my lactose.I head home and work on a painting project. I do not paint a lot, but I’m trying out different artistic styles to reengage myself. I like to reserve Sundays for hobby-hobbies and not work-hobbies. Today, this means watching Real Housewives of Potomac, painting, and eating some FitJoy Dijon-mustard pretzels with basil aioli. I also make myself a roasted dandelion tea.

My friend Clara comes over later with wine. She’s been very supportive over these last four years. Clara’s dad is super into wine. He gave her this bottle to drink with me for a post-getting-rid-of-my-Secret-Service celebration. A very mixed-emotions bottle.

Clara just moved into a new apartment, and we haven’t seen each other in a while, so we’re in desperate need of a catch-up. Eventually, we go get some vegan Thai food at May Kaidee. I take my red curry to go and pick up some tofu to add on the way home. I eat on my couch with my dog and drink a Stella while watching that episode of The White Lotus. Good night.

More Grub Street Diets

- Sauerkraut Fish Gets Headliner Treatment in the East Village

Photo: Grub Street Last week, on the stretch of Third Avenue just below 14th Street, a new restaurant opened with a name that may seem curious to anyone who’s unfamiliar: Sauerkraut Fish. It conjures Bavarian bouillabaisse, but the phrase is a common translation for the Sichuan dish suancai yu, or “sour-vegetable fish.” The sour vegetable in this case is pickled mustard greens, a member of the cabbage family, hence “sauerkraut,” though suancai is much saltier, and drier, than the German stuff with a cruciferous, earthy depth that permeates this fish stew.

Sauerkraut Fish, the restaurant, is mall-bright and lined with orange banquettes that sharply contrast the teal of Fantuan delivery bags waiting at the host’s stand. The menu is centered on the house specialty, in original or spicy — with mix-ins like vermicelli or mushrooms — served in a massive bowl, even the single portion, for $26. It’s filled with sliced white fish surrounded by a golden, greens-dappled broth and a pile of dried red chiles in the center. The poached slices of flaky snakehead fish — like a less muddy catfish — go gelatinous by the skin, which has a soft chew. The combination of seafood stock and umami-dense pickled greens is pungent, tangy, and steamy, like taking a warming swig from a jar of peperoncini.

In The Food of Sichuan, Fuchsia Dunlop dates suancai yu’s origin to the 1980s, when it “became all the rage in urban Chongqing, and later in Chengdu, in the 1990s.” Here in New York, the dish is available, though it’s hardly a mainstay: At Szechuan Mountain House, which has a few locations around town, it goes by Fish in Sour Cabbage Soup; Uluh on Second Avenue serves flounder with homemade pickled cabbage. So I was surprised to see sauerkraut fish as a headliner in non-Chinatown Manhattan. Sauerkraut Fish offers enough dishes to function as a regular Sichuan restaurant and delivery-app go-to, but nobody dining inside the restaurant treats it that way. When I went, every table had a bowl of brothy fish stew.

Outside Manhattan, Nai Brother, with locations in Borough Park and Long Island City, just opened on the Upper West Side about a week ago. Flushing is home to Fish with You, Seven Fish Cuisine, and Tai Er, in the Tangram mall, where 12 other groups were ahead of my party on the wait list this past Saturday night.

A glass wall between the restaurant and mall gives a window into the pristine Tai Er kitchen to the path of shoppers on the other side. I watched two synchronized cooks prepare sauerkraut fish, one hoisting a raft of poached seafood with a wok-size strainer and arranging it all in the center of an ample dish of soup strewn with wilted greens that their partner had just poured, followed by a bubbling waterfall of oil into which the chef had tossed a scoop of whole dried chiles and green peppercorns from a large wooden bin next to the station; it took approximately 30 seconds. This efficiency is no doubt owing to experience: While Tai Er Tangram was its first restaurant to open in America, the company operates 600 locations across eight countries with logistics that include a dedicated farm for mustard greens in Yunnan Province that are pickled at a facility in neighboring Sichuan.

Those greens slightly disappeared in the soup compared to the version at Sauerkraut Fish, where the pickle is saltier and more robust in addition to being cut into larger pieces. I preferred the spicy broth at Tai Er, however, which has a more potent peppercorn buzz, an effect that was elevated to its final form in an order of Sichuan peppercorn fish. It’s bathed in a smooth gravy containing a dose of aromatic green peppercorn that refreshes as it numbs — and it’s already my pick for au poivre of the year.

More New Bars and Restaurants

- The Long and Short of Radio Bakery’s New Location

Photo: Grub Street It’s clear we bear some responsibility for the line that has recently begun to fascinate Prospect Heights neighbors. When Grub Street called Radio Bakery’s turkey-pesto sandwich the best sandwich of 2024, we weren’t alone — plenty of our fellow omnivores had been singing Radio’s praises, too. So of course a queue formed outside Radio’s first location, on India Street in Greenpoint, which led the bakery to specify on its menu when certain items would go on sale (croissants at 7:30 a.m., non-croissaint pastries in the “late morning,” focaccia at 10 a.m., sandwiches at 11). When each would sell out, of course, was anyone’s guess. You’d try your luck and bring a book.

Finally, after months of anticipation, Radio’s second location opened in Prospect Heights, taking up the Underhill Avenue space that once housed a Blue Marble Ice Cream. (Radio is far from the only hype bakery to contend with rabid demand and not even the only one to expand on the strength of it; Brooklyn Heights’s L’Appartement 4F recently opened its second location in the West Village.) Whether doubling its footprint has alleviated pressure on the original I can’t say, but I can tell you this: At 12:18 p.m. on a Thursday during opening week, I was the 18th person on the line, which snaked well past the entrance, down to the coin-op laundromat three doors down, from whose window a woman warily eyed the assembled waiters: a dad with two kids and a stroller, another fuzzy-jacketed man with a fuzzy-onesied baby strapped to his chest, a variety of 20- and 30-somethings in carpenter jeans and Birkenstock Bostons, a pretty young woman in a banana clip who stepped away momentarily to take a selfie against the bakery’s glass-front doors.

This was, comparatively speaking, nothing. The Brooklyn Eagle reported a line 70 strong on the bakery’s opening day at the beginning of the month. I’m glad to add that my own wait was much shorter: At 12:33 p.m., I was safely out of some drizzle and inside the space, which is larger and lighter than Greenpoint’s. In the open kitchen at back, a team of bakers piped pistachio cream into and onto hulking croissants. Up front, we formed another line around the counter and ordered cafeteria style. “Has it been like this all week?” I asked the woman who rang me up. “Pretty much,” she said.

Expansion hasn’t affected quality as far as I can tell. I enjoyed the turkey sandwich as I always do, with its fearless embrace of garlic, and a recommended spicy tofu sandwich as well, which had a nice chile spice and maybe a little too much tahini. I generally prefer Radio’s breads to its pastries: Its locally famous brown-butter corn cake is a little puddingy and underbaked for my tastes, and its chocolate-chunk cookies are good, but standard, coffee-shop fare. All of it comes, understandably if frustratingly, at new-standard prices. I spent $50 and change on two sandwiches and three pastries.

If I lived and worked in Prospect Heights, I could easily imagine being a regular visitor, strolling up from Grand Army Plaza for a sandwich treat now and again. And I’d never begrudge Radio, or any of its compatriots, its success. But at a certain point, the hype cycle eats away at its victims on both sides, the vendors and the customers. At what point, we have to wonder, is the product being offered the bread or the wait? I took my box of treasures to one of the two sidewalk tables. “Good?” I overheard from a couple walking by. “Supposed to be very good.” Another woman trundled by. “There’s still a huge line,” she said into her cell.

More Eating New York

- Alinea Comes to New York, at Last

Photo: Lanna Apisukh Rain came down in sheets on the opening night of the month-long residency of Alinea at Olmsted. Grant Achatz’s high-caliber, hypertechnical Chicago restaurant Alinea turned 20 years old this year, and since Greg Baxtrom, chef of Brooklyn’s Olmsted, had been there at the very beginning, Achatz was visiting his mentee to celebrate. “I began thinking how many people have come through the restaurant and gone on to do amazing things,” Achatz explains. “I wanted to involve the alumni. Greg was on my shortlist.”

Baxtrom was a cooking-obsessed 19-year-old Eagle Scout looking to interview the then-unknown Achatz when he walked into the restaurant in 2005. He ended up working in the kitchen for three and a half years, leaving after he’d risen to become a sous-chef. When, nearly a decade later, he opened Olmsted, Alinea’s influence was felt in the playful preparations like a Christo-orange carrot crêpe and a sweet-pea falafel. “The best compliment I got early on,” Baxtrom says, “was it felt like if Alinea and Blue Hill Stone Barns had a casual baby.”

The demand for seats at the collaboration has been extraordinary. As soon as the residency was announced in February, tickets, which cost $455 for one person, sold out. (More will be released gradually through the restaurant’s run.) Alinea’s residency in New York goes far beyond the usual pop-up M.O.; the whole space has been reimagined. The private dining room has been turned into an old-timey library. The covered backyard is transformed into a greenhouse. And the main dining room has become some kind of futuristic vessel. “We did this all in two days,” says Baxtrom, with equal measures of exhaustion and pride. “Short runway,” agrees Achatz.

Alinea is known for a certain vision of maximalist modernist cooking. The collaboration keeps the mondo aesthetic going. The dinner unfolds over five locations and offers nearly 20 courses. It has many layers, no small amount of theatricality, and a soundtrack that includes both the Kronos Quartet’s “Requiem for a Dream” and the Beastie Boys’ “No Sleep Till Brooklyn.” Jaywalking is involved. So are quatrains, black lights, truffles, caviar, and charred Arctic char. There are four seatings each night, from 5:30 to 9:15, with between 20 and 24 guests per turn. Almost the entire Alinea staff has relocated for the month, many doubled up in Airbnbs around the city.

Every meal starts in the library. On an antique desk, an Underwood typewriter has a single sheet of paper in its maw. “Take What Is Yours.” An open guest book sits on an armchair, fountain pen uncapped. From a record player next to a sepia-toned globe, lit by long tapered candles, Leoš Janáček’s “Sinfonietta” crackles and pops. The first course is had by the window where a contraption made of multiple antennae sits. At the tip of each rod, like the inflorescence of a cattail, is a tiny square of everything bagel topped with lox, pickled red onion, a fried caper, whipped cream cheese, and dill.

On the bookshelves, beside the Escoffiers and Phaidons, sit multiple novels by Haruki Murakami. They are large with bright-red spines and bold white letters. A suited server instructs guests to pluck the book from the shelf. Achatz says he was inspired by a particular scene in Murakami’s 2002 novel Kafka on the Shore. “It’s about time and reflection and projection, so we wanted to have elements of the past, the present, and future,” he told me after the meal. These are not books at all but booklike boxes. Inside the hollow cavity is a small flashlight, a teensy-weensy pizza box, and a card on which is written a pair of rhyming couplets. “You’ll need the flashlight later,” instructs a server.

Inside the pizza box is the second course: a small triangle of rice paper (very thin crust!) on which the flavors of pizza — dehydrated ground pizza crust, mozzarella powder, tomato powder, and a bunch of other powders — are affixed. “Let it dissolve on your tongue,” says another server. (There are many servers.) The final course in the library, melding future and past, is a “Chicago dog”: two discs of translucent hot-dog water — made of charred hot-dog stock run through a rotary evaporator — topped with a tiny brunoise of tomato, compressed onion, a slice of sport pepper, and a neon-green relish fluid gel. Each sits atop a monocle, which itself rests upon a postcard of Chicago.

Hot dog slurped, we are bidden to examine the poetry written on the card found inside the faux Murakami: “Mushrooms sprout where shadows creep / The path is dark, the roots run deep. / Take your flashlight, hold it tight — You’ll need its glow to guide the night.” With that, we’re led through a moss-lined hallway into the back garden. Along the walls, in custom-made glass vessels, are puffed porcini-mushroom crisps with pine-nut mushroom butter. We pluck and eat, deposit our flashlights, and continue into the backyard.

This sets off an unceasing procession of courses; five courses are served in the back garden. Few involve a traditional knife and fork. “The monotony of fork, knife, and spoon that we do our whole lives,” says Achatz, “it becomes second nature. We have to break that. It’s a little alarming, a little different.” Caviar, for instance, that sits atop a disk of pineapple gelée studded with vesicles of finger lime, arrives in a curved pebbled glass meant to tactilely mimic the experience of caviar itself. That vessel, alongside 3,000 pounds of other material, arrived in a shipping container and two vans from Chicago a few days before. A course called “explosion,” an Alinea mainstay, consists of a black truffle, Parmesan raviolo served on a single spoon with no plate at all. “Make sure you seal your lips around it,” says the server. Brown-butter fried frog legs are served beside potted Brooklyn evergreens doused in scented water. A nod to Chinese takeout, beef and broccoli (Australian Wagyu short rib, broccoli stem, broccoli purée, fried florets, razor-shaved broccoli cells) is served atop a hot slab of concrete and finished with a Brooklyn Brewery beer gelée “graffiti.”

After the concrete is cleared, the meal moves to the main dining room of Olmsted. The walls are lined with aluminum foil. It feels like being in a kid’s lunch sack. Between the tables, kept taut by hidden strings, are sheets of translucent fabric.

Everyone sits before large, opaque glass columns. “All rise,” calls a server. Dutifully, everyone shuffles to their feet. “Sometimes, you have to confront your fears,” he says, “before taking what is yours. So please punch the top of the cylinder and enjoy.” We punch open the top of the cylinder, where a solitary prawn, skewered by a vanilla bean, is our reward. Having confronted our fears, we eat the prawn and sit down again. Maple-syrup-cured charred Arctic char arrives on a toadstool-like pedestal. Flipped over, one sees secreted into the empty space char roe and carrot curry pearls held in a gelée. In another, cauliflower is served with goat-milk curds masquerading as floret. Then an Alinea classic — Hot Potato/Cold Potato — is presented in a complicated vessel, a bowl that needs directions that, when properly operated, plunges a sphere of hot potato into a cold potato soup. The final dish, one that Baxtrom used to prepare at Alinea, is squab accompanied by a realistic strawberry made of beeswax, strawberry purée, and lemon balm.

Then it’s time to go outside, where employees gamely hold umbrellas on the deserted street. (By this time, it is around midnight.) We cross the street into Amorina, whose owner is on a monthlong Alinea-sponsored vacation. The entire space is shrouded in white fabric. The tables are white; the staff wear white slippers, and the floor is photo-studio white too. A procession of chefs stream from the kitchen in single-line formation. Each holds a yellow chalice that they set upon the table. In it sits a baked Alaska made with barrel-stave-smoked ice cream. They torch the meringue. It’s all very The Menu meets Wild Wild Country. In front of each table, the chef swoops and swooshes ruby-red syrups and taupe puddles. This is the famous Paint dessert (known in the kitchen as the Mat Set). They shuffle away. Suddenly, the lights change to black light and the Beastie Boys’ “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” begins to blare. In the light, the antique glass goblets glow a psychedelic yellow. The cherry swirls emit an Upside Down glow, and the banana sauce radiates a faint uranium glimmer.

By the time the meal ends, it is well past midnight. The rain has stopped. It’s hard to know what to feel. Full? Yes. Satisfied? Maybe. Where’s the line between silly and spectacular, try-hard and transcendent? It has been washed away. The effort is heroic; nothing here is nonchalant, and though the experience is seamless, to think of the sheer amount of work — the glass polishers ceaselessly cleaning, the servers trotting back and forth across Vanderbilt in the rain, the chefs slipping in and out of their slippers, the combined kitchen staff, the mass of allusions made and gelées set — it’s impossible not to be awed. In the words of Murakami, “Once the storm is over, you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure, in fact, whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.”

Related

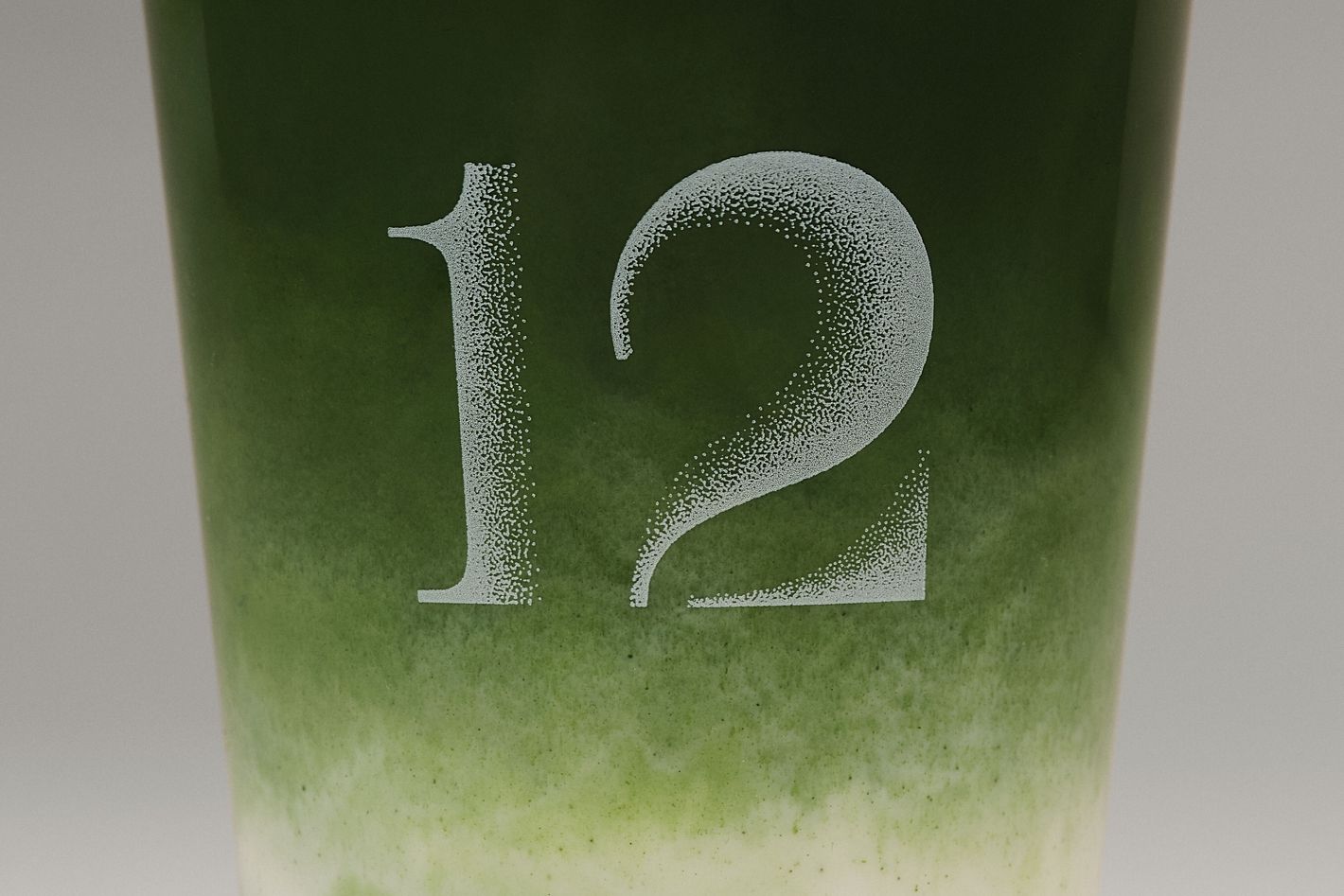

- Is New York About to Go Crazy for This Matcha Latte?

Photo: Michael Carbone The Hotta family has been growing and selling tea in Japan for five generations, a period of time that stretches across 180 years. For 55 of those years, Haruhide Morita has been tea master and special adviser. And four years ago, Alan Jiang was still an undergrad at Cornell University when he began thinking about how to translate that history and tradition into a modern business. This week, the group will open 12 in Noho, a new café and retail shop designed to do that via matcha lattes, vibrant ice cream, and experiential tastings.

This town, of course, has plenty of matcha: There are at least seven Cha Cha Matchas and eight Matchaful cafés dotted around Manhattan and Brooklyn. There are two outposts of Kettl and one Setsugekka, both excellent. Then there’s every other coffee shop and tea parlor in New York. Undoubtedly, this city is contributing to the current global-matcha shortage.

But 12 has the benefit of working directly with a family of farmers, just one of the ways this café is different. Jiang wants to make something that is intentionally cerebral but nevertheless approachable and fun. In addition to Jiang and Morita, the team at 12 includes Dr. Christopher Loss, a professor in the food-science department at Cornell; Francisco Migoya, currently the head of pastry at Noma; the French design collective Cigüe, whose work you’ve seen if you’ve walked into an Aesop store or the % Arabica in Dumbo; and Grace Phillips, the general manager, who has worked in hospitality around the city for years.

The attention to detail is evident as soon as you enter the two-story café. The color green is everywhere, most prominently on the countertops made of lava stone from a quarry in Volvic, France, that’s been glazed in an emerald-colored enamel created specifically for 12. The clay walls are painted in a gentle green-putty hue, meanwhile, and “we also played with filtered light to subtly mimic the dappled shading of tea fields,” says Camille Bénard, one of Cigüe’s co-founders.

Above the bar are three large glass vessels, a little alien in nature. “Water became something that we are obsessed with,” Jiang explains. The vessels contain two-foot-long sticks of binchotan charcoal that filter NYC tap, gently releasing bubbles throughout the day. “The binchotan makes a very nice little catacomb that allows the water to quiescently filter through,” says Loss, who studies flavor science and the sensory qualities of food. He found that after eight hours with the sticks, the pH of the water became slightly more alkaline, which helps to round out the acidity of the tea.

Photo: Michael Carbone Jiang says he wants guests to focus on all three elements of matcha: the tea, the water, and the air. “Not just in terms of the flavor itself,” he says, “but the visual to be able to prime the senses.” What does that have to do with ice cream? Migoya — from Noma — was introduced to Jiang by Loss, who worked with him at the Culinary Institute of America decades ago. He’s devising sweets that put Morita’s special blends to culinary use. I tasted Migoya’s matcha ice cream both in frozen scoop form as well as freshly spun in the ice-cream machine, which was full of flavor and verve. Migoya has also engineered a bright-green Basque cheesecake and is working on matcha chocolate, trying to find the right balance of the astringency between the tea and sugar.

In addition to in-store tastings, an iced matcha latte will likely be the main attraction at 12. The tea is whisked under a spotlight and poured over milk — Battenkill for dairy, Califia Barista Blend for oat — for a drink that is grassy, creamy, and spring-pea-like in its savoriness. Taking into account the consideration that has gone into each element, the price — $7 — seems almost like a deal. It is also, as Morita sees it, important to create a way forward for matcha. “If it’s something good, it should naturally expand,” he says. “There’s a part of me that feels we should continuously promote these good things, otherwise, they’ll disappear.”

More New Bars and Restaurants

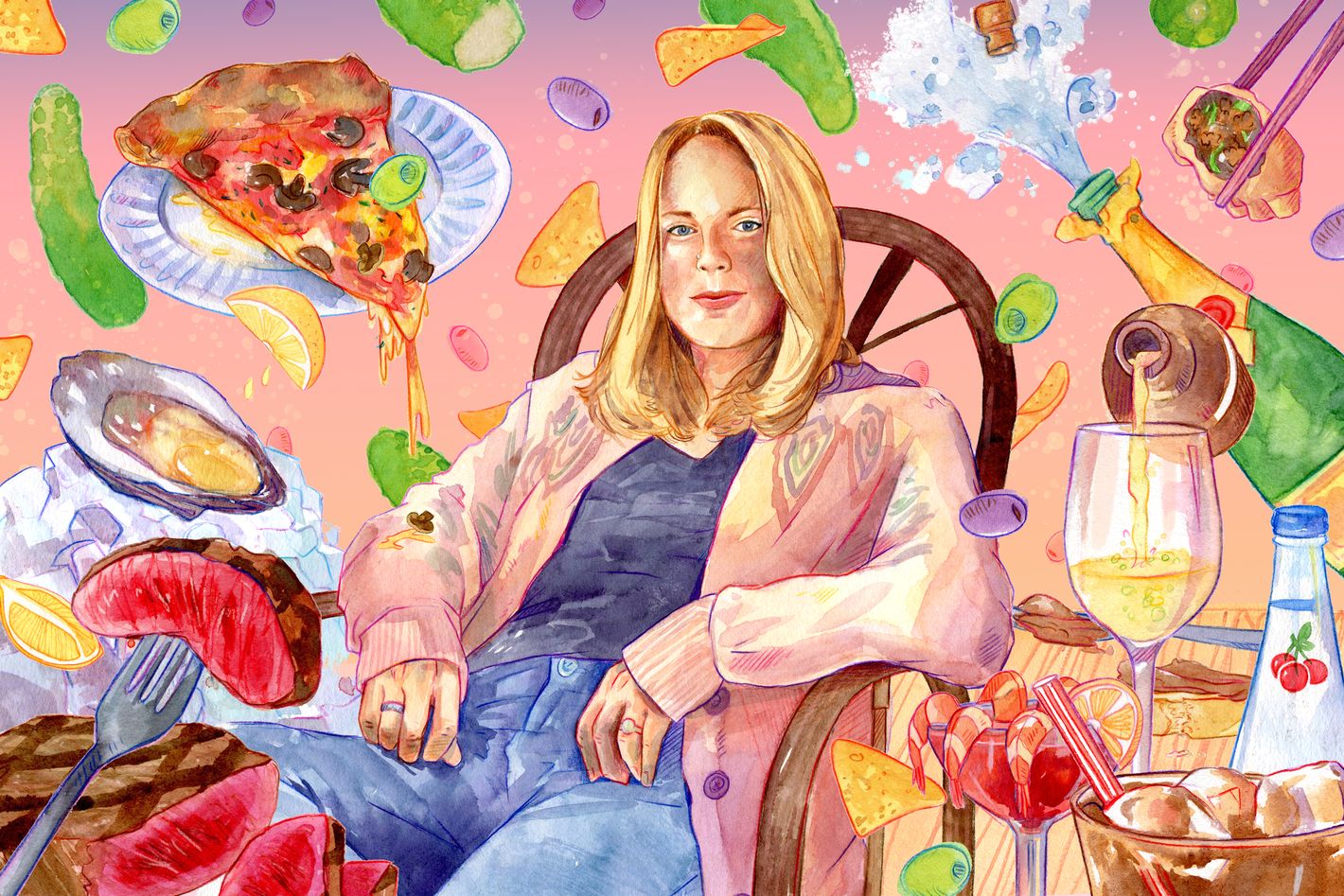

- Hannah Selinger Has a Fruit Problem

Illustration: Sarah Kilcoyne Hannah Selinger has spent the last decade writing about food and restaurant life. But long before that, she was a sommelier, and now that work has become the basis of her first book, Cellar Rat: My Life in the Restaurant Underbelly, which debuts next week, and which, last week, caused a food-world stir after journalist — and Grub Street contributor — Joshua David Stein deemed it a “mix of Joris-Karl Huysmans, M.F.K. Fisher, and Regina George” (now Selinger’s Instagram bio) in a harsh review for the New York Times. Selinger was quick to respond, attributing the review to a “mediocre white man” on her website. In between leftovers in her Boxford, Massachusetts, home, though, she says she’s already moved on: “I don’t give unethical, misogynist commentary on my work oxygen,” she says. “And I definitely don’t give it rent-free space in my head.”

Sunday, March 2

I have thought long and hard about how to discuss the problem of coffee with my readership, but, in the interest of true transparency, I’m going to throw caution to the wind. This is, after all, an unveiling of my true preferences, and my true preference when I wake up every morning is a cup of Lavazza Super Crema, ground to order in a DeLonghi Dinamica automatic espresso machine, and then ruined, some might say, with an utterly grotesque amount (let’s say three to four tablespoons) of Coffee-Mate Sugar-Free French Vanilla Creamer.I make green-olive cream cheese, at the request of my 6-year-old son, and we all eat bagels for Sunday-morning breakfast. I’m embarrassed to admit that I keep Thomas’ bagels in the house. They are bad — like, horribly bad — but I eat mine toasted with thinly sliced red onion on top.

We were supposed to go skiing, but it has been kind of a bummer of a season, between the unpredictable snow and high-wind warnings, so instead we’re staying home. My kids are temporarily occupied with my old Calvin and Hobbes, but they eventually get bored and ask me to cut up an entire cantaloupe. We eat the whole thing. Fruit doesn’t stand a chance in this house. I can’t walk into an H Mart without spending $50 on mangosteen, but that’s another story.

Now, I’m down to only apples and string cheese and stale Twizzlers in the fridge (I like them stale and cold), so I convince everyone to get dressed so that we can go to Trader Joe’s, which I already know is going to be crowded and horrible on a Sunday, but it gives me a chance to think about dinner. My kids pick all of the most expensive, out-of-season fruit they can find, like blueberries and raspberries and a white strawberry that TJ’s markets as a pineberry and another cantaloupe, obviously; I also grab a cold-pressed pineapple juice so that I can chug it in the parking lot.

When we get back home, I make Kraft macaroni and cheese for my kids. I eat several spoonfuls out of the pot and then eat three giant leftover turkey meatballs from a few nights before.

For dinner, I make minestrone soup, a riff on the old Mollie Katzen recipe from the Moosewood Cookbook. This is not a seasonal soup. There is no reason to make it in March. It’s made with eggplant, green pepper, zucchini, and other things that are definitely not grown here. But it’s also a way to get vegetables into my family members, and I’m a fan of anything that can be cooked in one pot (two if you count the pasta, which, fine, I cook separately).

My husband and I turn on the Oscars, and I decide that I haven’t had enough to eat. Thankfully, we have pigs in a blanket in the freezer. I eat them with an enormous side of French’s yellow mustard. I have no idea why I don’t have heartburn.

Monday, March 3

I wake up extremely thirsty, so the first thing I do is pour myself a giant glass of ice water. I follow this up immediately with my good-bad coffee. I’m usually hungry in the morning, but the effect of eating 20 pigs in a blanket at 9 p.m. has curbed my morning appetite. Around 8, I stand outside in the freezing cold with my kids at the bus stop.Mondays are big admin-task days for me. Eventually, I look up, and it’s suddenly 10:30 and I need to eat. Avocados and eggs are almost always my fallback when this happens. I mash one entire avocado very quickly with the back of a spoon, add salt (kosher, Morton, if you must know), ground pepper, and Frank’s Red Hot, and then top it with an egg that I very briefly fry. I eat all of this standing over the stove, with more Frank’s and, yes, a spoon. And I do not do the dishes.

About an hour later, I’m back in the kitchen, hand in my stash of Trader Joe’s dark-chocolate peanut-butter cups. I’m actually not a huge fan of peanut butter, and I don’t ordinarily like peanut-butter-flavored desserts, but there’s something about the texture of these and the ratio of chocolate to filling. I also eat a chunk of a torn baguette, not yet stale. I try to put butter on it, but realize that the butter that I keep on the counter tastes weird. I spend an inordinate amount of time Googling “can rancid butter give you food poisoning?” before deciding that I’m fine.

When my kids come home from school at 3, they are ravenous. One of them wants plain Cheerios with milk (hard pass), and the other wants grapefruit. I cut myself a giant pink grapefruit, too, and add a diabetes-inducing amount of sugar to it.

For dinner, it’s seared chicken thighs cooked over rice with a really lemony, mustardy, shallot-y salad on the side, inspired by a dinner I recently ate at Bernadette in Salem. (I add some thinly sliced cucumbers, rainbow carrots, and halved grape tomatoes for contrast, but it’s mostly just a red-leaf-lettuce mix with a whole bunch of dressing.)

I’m out of parsley, so I also make a gremolata with lemon zest, garlic, and coarsely chopped grilled green olives that I got as a holiday gift, and it’s a really nice, bright contrast with the salty, fatty chicken. The olives have these tiny little grill marks on them, like the kind you find at the bazaars in Turkey, but I’m pretty sure these are from HomeGoods. Bonus points, because my kids eat most of the food groups here (olives, rice, chicken, cucumbers, tomatoes), although they will not touch lettuce, unlike my Russian tortoise, Gromit, who dines on it exclusively. I eat this all with a very cold and crispy Diet Coke in a double-walled Tervis tumbler that says Kiawah Island on it, which is super-ugly but also the only vessel in my house that reliably keeps my drinks cold.

I have to catch up on The White Lotus and Saturday Night Live, and I do both, predictably from my couch, surrounded by three different flavors of Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams because I can’t make a decision: Coffee With Cream and Sugar, Brambleberry Crisp, and Wildberry Lavender.

Tuesday, March 4